Days on cruise: 166

Distance traveled: 34.1 miles

Travel Time: 4 hrs, 12 mins (6:36 including locks)

Total trip odometer: 3,345 statute miles

An addendum to yesterday’s post: After the kids left, Cathryn went ashore to get rid of garbage, so met the owner of the marina, another Bob. After chatting a bit, Bob said he was going into town to meet his girlfriend for dinner, and if we wanted to drop him off at the restaurant, we could keep his van for the rest of the evening to run some errands. Wow! We keep meeting the nicest folks who do stuff like this, knowing they’ll never see us again and there’s nothing in it for them. But Bob and Harborside Marina 14 miles south of Joliet sure earned this mention! We stocked up on groceries as well as went to Wal-Mart in search of some camera stuff (no luck).

At midnight we woke to some serious rocking and rolling on the water. Bob went to investigate, and it turned out we were experiencing a squall. The lightning and thunder were continuous, the rain was pounding, and the wind was blowing so hard we hoped the skimpy posts (no cleats) to which our boat was tied would hold. Bob sat on the flybridge for 30 minutes til it subsided, but it sort of ruined his sleep for the night.

This morning the weather remained windy and nasty, so we stayed at the dock an hour longer than planned to see if things would calm down. When they did, we called the Dresden Lock a mile down river and learned there would be no wait to enter and get locked down. Hurray!

The scenery improved with few industrial facilities and lots of trees, above.

Many of the bridges all along the Loop have “air clearance gauges” you can check in advance with your binoculars to see how high the bridge is at the current water level. This tells you whether you can safely make it under, or whether you need to call a bridge tender to open it, if it’s that type of bridge. As you see on this gauge, the current clearance under the bridge is more than 50 feet, but apparently at times, probably during Spring flood season, there can be 20 feet or less! We were amazed to see all the buildings and facilities which would be under water if it gets that high.

While it’s a little intimidating to see these behemoth tows pushing multi-wide barges toward you, there are clear protocols for communicating with and passing them which make it safe. We have AIS (Automatic Identification System) installed on our electronics, and Bob set the sensitivity at a 2-mile distance. When the AIS detects a tow within that range, it makes an audible sound on the chartplotter and also shows the location and name of the approaching vessel, as well as how many minutes or seconds until we collide if we don’t take steps to pass safely. It even shows boats that are around a bend in the river that can't yet be seen. So we call the tow, by name, on our VHF radio, tell them our location and how far we are from them, and ask them whether they want us to pass on their port or starboard side. The biggest vessel always gets to decide!

We’re amused to learn they respond in more friendly fashion to Cathryn’s voice than Bob’s, but in any case, they’re always appreciative and give us clear direction in tow lingo. “On the one” or “one whistle” means we stay to the right side of the channel leaving them to our port; “two whistles” means we go to the left side of the channel and leave them to our starboard side. We’ve heard them chastise boaters who don’t know what this means, so it’s worth learning!

The tugs have a HUGE prop wash that leaves strong currents and whirling eddies in their wake for about 1,000 feet, so we steer carefully after passing them.

This summer’s drought devastated the Midwest agricultural scene. The fringe of trees along the river shoreline is backed by mile after mile of dead corn fields, the result of no rain.

This afternoon we spent two hours sitting idle above the Marseilles Lock while a large tug with 4-by-2 barges entered the lock ahead of us, split the barges in order to fit them all in at once, then maneuvered them to both walls, locked through, then reconnected the barges to proceed. It must be a tedious process for the tow captains!

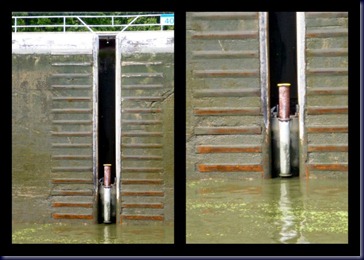

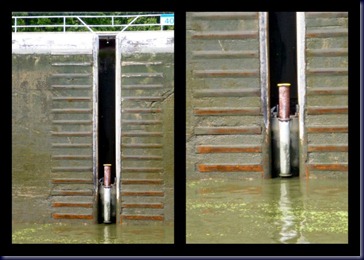

So far all of the locks we’ve encountered south of Chicago have both floating bollards (below) as well as ropes hanging down from the wall. We much prefer the bollards. With these, we position the boat against the wall so the middle of the boat is adjacent to the bollard, throw one line around the top of the bollard, and as the water level drops, so does the bollard inside the recessed channel. We don’t have to adjust our lines to make them longer as we would if we were hanging onto lines at the top of the lock wall. Simple! We have, however, been warned by one lockmaster to always keep a knife close at hand in case the bollard gets stuck and stops floating down. If that happens, we’re to rapidly cut our line off and float on the water without any attachment to the wall. Yikes! Hope that never happens.

This huge old tug has been turned into a riverside café.

Five miles before the Marseilles Lock we passed a canoe on the river, the first we’ve seen. As already described above, we had to wait two hours before we could enter the lock. During that time, this canoe caught up with us!

He pulled into the lock right behind us and we had the chance to talk with him for 20 minutes while the water dropped. It turns out he’s also doing the Great Loop!!! Incredibly, he began his Loop in Grafton, Illinois only three weeks (at his speed) south of here last October 2011 and will finish soon. Bill told us he averages 25 miles per day, budgeted no money for fuel (of course) or lodging, camps on the shore most nights but occasionally gets invitations to stay in someone’s home, and has only a cell phone and camp stove with propane canisters on board, no VHF radio or other amenities.

Bill also described being denied permission to transit the Electric Fish Barrier (see post two days ago), so had to CARRY, by himself, his canoe and belongings along the shoreline to bypass the 1/4 mile electrified segment. Amazing!!! His biceps show what he’s been doing the past 11 months. He’s a cheerful, interesting guy. Makes us feel like wimps for thinking we’re living in small quarters!

At the end of the day we tied up on the Ottawa town wall, yet another free wall with electricity, but no water. We’re happy to be able to run the air conditioner as it was close to 90, both temperature and humidity, again today.

Distance traveled: 34.1 miles

Travel Time: 4 hrs, 12 mins (6:36 including locks)

Total trip odometer: 3,345 statute miles

An addendum to yesterday’s post: After the kids left, Cathryn went ashore to get rid of garbage, so met the owner of the marina, another Bob. After chatting a bit, Bob said he was going into town to meet his girlfriend for dinner, and if we wanted to drop him off at the restaurant, we could keep his van for the rest of the evening to run some errands. Wow! We keep meeting the nicest folks who do stuff like this, knowing they’ll never see us again and there’s nothing in it for them. But Bob and Harborside Marina 14 miles south of Joliet sure earned this mention! We stocked up on groceries as well as went to Wal-Mart in search of some camera stuff (no luck).

At midnight we woke to some serious rocking and rolling on the water. Bob went to investigate, and it turned out we were experiencing a squall. The lightning and thunder were continuous, the rain was pounding, and the wind was blowing so hard we hoped the skimpy posts (no cleats) to which our boat was tied would hold. Bob sat on the flybridge for 30 minutes til it subsided, but it sort of ruined his sleep for the night.

This morning the weather remained windy and nasty, so we stayed at the dock an hour longer than planned to see if things would calm down. When they did, we called the Dresden Lock a mile down river and learned there would be no wait to enter and get locked down. Hurray!

The scenery improved with few industrial facilities and lots of trees, above.

Many of the bridges all along the Loop have “air clearance gauges” you can check in advance with your binoculars to see how high the bridge is at the current water level. This tells you whether you can safely make it under, or whether you need to call a bridge tender to open it, if it’s that type of bridge. As you see on this gauge, the current clearance under the bridge is more than 50 feet, but apparently at times, probably during Spring flood season, there can be 20 feet or less! We were amazed to see all the buildings and facilities which would be under water if it gets that high.

While it’s a little intimidating to see these behemoth tows pushing multi-wide barges toward you, there are clear protocols for communicating with and passing them which make it safe. We have AIS (Automatic Identification System) installed on our electronics, and Bob set the sensitivity at a 2-mile distance. When the AIS detects a tow within that range, it makes an audible sound on the chartplotter and also shows the location and name of the approaching vessel, as well as how many minutes or seconds until we collide if we don’t take steps to pass safely. It even shows boats that are around a bend in the river that can't yet be seen. So we call the tow, by name, on our VHF radio, tell them our location and how far we are from them, and ask them whether they want us to pass on their port or starboard side. The biggest vessel always gets to decide!

We’re amused to learn they respond in more friendly fashion to Cathryn’s voice than Bob’s, but in any case, they’re always appreciative and give us clear direction in tow lingo. “On the one” or “one whistle” means we stay to the right side of the channel leaving them to our port; “two whistles” means we go to the left side of the channel and leave them to our starboard side. We’ve heard them chastise boaters who don’t know what this means, so it’s worth learning!

The tugs have a HUGE prop wash that leaves strong currents and whirling eddies in their wake for about 1,000 feet, so we steer carefully after passing them.

This summer’s drought devastated the Midwest agricultural scene. The fringe of trees along the river shoreline is backed by mile after mile of dead corn fields, the result of no rain.

This afternoon we spent two hours sitting idle above the Marseilles Lock while a large tug with 4-by-2 barges entered the lock ahead of us, split the barges in order to fit them all in at once, then maneuvered them to both walls, locked through, then reconnected the barges to proceed. It must be a tedious process for the tow captains!

So far all of the locks we’ve encountered south of Chicago have both floating bollards (below) as well as ropes hanging down from the wall. We much prefer the bollards. With these, we position the boat against the wall so the middle of the boat is adjacent to the bollard, throw one line around the top of the bollard, and as the water level drops, so does the bollard inside the recessed channel. We don’t have to adjust our lines to make them longer as we would if we were hanging onto lines at the top of the lock wall. Simple! We have, however, been warned by one lockmaster to always keep a knife close at hand in case the bollard gets stuck and stops floating down. If that happens, we’re to rapidly cut our line off and float on the water without any attachment to the wall. Yikes! Hope that never happens.

This huge old tug has been turned into a riverside café.

Five miles before the Marseilles Lock we passed a canoe on the river, the first we’ve seen. As already described above, we had to wait two hours before we could enter the lock. During that time, this canoe caught up with us!

He pulled into the lock right behind us and we had the chance to talk with him for 20 minutes while the water dropped. It turns out he’s also doing the Great Loop!!! Incredibly, he began his Loop in Grafton, Illinois only three weeks (at his speed) south of here last October 2011 and will finish soon. Bill told us he averages 25 miles per day, budgeted no money for fuel (of course) or lodging, camps on the shore most nights but occasionally gets invitations to stay in someone’s home, and has only a cell phone and camp stove with propane canisters on board, no VHF radio or other amenities.

Bill also described being denied permission to transit the Electric Fish Barrier (see post two days ago), so had to CARRY, by himself, his canoe and belongings along the shoreline to bypass the 1/4 mile electrified segment. Amazing!!! His biceps show what he’s been doing the past 11 months. He’s a cheerful, interesting guy. Makes us feel like wimps for thinking we’re living in small quarters!

At the end of the day we tied up on the Ottawa town wall, yet another free wall with electricity, but no water. We’re happy to be able to run the air conditioner as it was close to 90, both temperature and humidity, again today.

No comments:

Post a Comment